The United States is more diverse than ever. For the first time, a majority of people under the age of 15 are non-white or Hispanic, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Diversity is our future.

In 2020, the twin forces of the COVID-19 pandemic and the racial justice protest movement focused overdue attention on long-standing racial health disparities. Skin, the largest organ of the body and the most visible, has perhaps never been such a hot topic. Dermatologists everywhere are seeing the effects on research and clinical practice. “There has been an explosion of interest in skin of color,” says Susan C. Taylor, MD, one of several experts highlighted in our feature whose pioneering efforts over the past two decades have helped lead us forward.

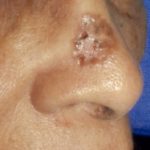

In this issue, New York-based health writer Sheryl Huggins Salomon highlights lessons learned, from clinical and demographic issues to risk factors, prevention and engagement with patients of color. Our experts also discuss the crucial need for more diagnostic images of skin cancer as it presents in patients with skin of color, to help educate medical professionals as well as the public.

The Skin of Color Revolution in Dermatology: Crucial Lessons Learned

By Sheryl Huggins Salomon

Lesion photos in this issue donated by Hugh Gloster, MD

It has been a mere 22 years since dermatologist Susan C. Taylor, MD, realized she had to do something about the profound lack of awareness in her field about diagnosis, treatment and research relating to diseases in skin of color. Much has happened in the timeline since then.

In 1999, Dr. Taylor and Vincent DeLeo, MD, then-chair of the dermatology department at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital in New York City (now Mount Sinai West), decided to create the Skin of Color Center there. “It was the first center of its type devoted to excellence in the diagnosis and treatment of skin disorders in people with skin of color,” she says. Five years later, Dr. Taylor felt more was needed, so the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) was born. “Our mission would be to promote research, educate about skin of color and mentor young people in the field of dermatology and in skin of color.”

Then in 2006, the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD) published “Skin Cancer in Skin of Color” by Hugh Gloster, MD, and Kenneth W. Neal, MD. PubMed lists 88 citations alone for this seminal continuing education article. It begins with a simple statement that encapsulates the stakes involved in educating physicians about the topic. “Skin cancer is less common in persons with skin of color than in light-skinned Caucasians but is often associated with greater morbidity and mortality.”

Yet, there remained a dearth of education in dermatology about diseases in more darkly pigmented skin, with few reference photos to go by. So “several of us wrote textbooks,” says Dr. Taylor. In 2009 she cowrote Dermatology for Skin of Color, with the late A. Paul Kelly, MD, who was editor-in-chief of the Journal of the National Medical Association from 1997 to 2004 and the first Black president of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. In 2011, Treatments for Skin of Color followed, cowritten with Sonia Badreshia-Bansal, MD, Valerie Callender, MD, Raechele C. Gathers, MD, and David Rodriguez, MD.

Still, more than a decade later, “There are just several of them, right? But now, the mainstream, well-known textbooks are including skin of color images in sections. So our goal is to have them integrated into all dermatology textbooks. And I think it’s definitely starting to happen,” says Dr. Taylor, associate professor of dermatology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. As an example, she points to Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin, now in its 13th edition, and its companion atlas. “For a number of years, the senior editor, Dr. William James, has made sure he included skin of color imagery.”

Today, there has never been more focus on skin of color in medicine. For the study and treatment of skin cancer, that interest meets the challenge implied in Gloster and Neal’s opening statement: closing the racial gap in morbidity and mortality. The greater amount of epidermal melanin in darker-skinned individuals may give them a greater degree of photoprotection, hence the lower incidence of skin cancer overall, according to the two doctors. However, it doesn’t prevent worse outcomes for people of color. It is therefore important to understand racial and ethnic differences in disease prevalence, progression, outcomes, presentation and engagement in treatment.

Dr. Taylor attaches the most urgency to detecting melanoma in skin of color. [Editor’s note: While Carcinomas & Keratoses does not usually cover melanoma, we felt it was crucial to include it in this comprehensive special issue on skin cancer in skin of color.] Certainly, it isn’t as prevalent. The rate per 100,000 white individuals is 27 times that of Black individuals in the U.S., according to National Cancer Institute data for 2017. There is a similar racial gap for Asians and Pacific Islanders; and the rate per 100,000 white individuals is still six times that of Hispanic individuals.

However, the relative five-year melanoma survival rate among non-Hispanic Black people is 66.2 percent, compared with 90.1 percent for non-Hispanic white people, according to research by MaryBeth B. Culp, MPH, and Natasha Buchanan Lunsford, PhD, published in 2019 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A separate in-press study published by JAAD this year found Asians and Pacific Islanders had a five-year melanoma survival rate of 77 percent, compared with 89 percent for white people.

“So here’s the thing. There are many people, laypeople of color, as well as dermatologists and primary care physicians, who do not think that people with darker skin tones develop melanoma. Well, that couldn’t be farther from the truth,” says Dr. Taylor. “Melanoma is deadlier — there are worse outcomes, we think — because it is diagnosed and treated at a later stage compared to people of Caucasian descent. We do not think that there are biological differences, although people are looking at that.”

When Culp and Dr. Lunsford looked at stages of progression, indeed, they found that non-Hispanic Black people were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to be diagnosed in later stages of spread (regional or distant metastasis). They also found that:

“What’s needed — and I’m sure there are people working on it — is to look at genetics and see if there are genetic mutations in Blacks who develop acral lentiginous melanoma,” says Dr. Taylor.

Acral lentiginous melanoma

Hypopigmented cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is another type of skin cancer that is more prevalent among Black people than it is among other racial groups, according to a 2009 continuing education article by Ginette A. Hinds, MD, and Peter Heald, MD, that was published in JAAD. To be sure, it is relatively rare. U.S. National Library of Medicine’s MedlinePlus guide states there are fewer than 4 cases per million of mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common subtype, in the U.S. each year. Yet according to Gloster and Neal, MF nevertheless affects Black patients at twice the rate of whites; and Hinds and Heald write that it follows a more aggressive course, with a higher mortality rate in Blacks.

While BCC outpaces cSCC in prevalence among white people, the opposite is true for Black and Asian Indian people, according to Gloster and Neal. That assessment has become popular wisdom in dermatology, but perhaps it bears a second look based on more recent research, says Adewole Adamson, MD, a dermatologist and assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School. “There’s some research that has shown that it is actually flipped.”

Dr. Adamson points to a cross-sectional analysis that appeared in August 2020 in JAMA Dermatology. Based on Optum data collected between 2012 and 2016, it found that BCC was more prevalent than cSCC in all races and ethnicities. The highest BCC to cSCC ratios were found in white women ages 18 to 39 (12.75) and Black women in the same age group (12.48). The ratios dropped with age, except in Asian men, who saw an increase between the 18 to 39 (1.69) and 40 to 64 age groups (2.51). The lowest ratio was found in Black adults, ages 65 years or older (1.16). The highest overall ratio of BCC to cSCC was found in Hispanic patients.

A cSCC on the scalp of a Black man

Pigmented BCC behind the ear

An important step toward improving outcomes for patients of color is educating both health-care providers and the public on what to look for, says Dr. Taylor. For instance, she says, “Melanoma commonly occurs on the back and legs of white men and women, but in people of color, it occurs on palms and soles and fingernails, as well as mucous membranes of the mouth and genital area.” It most often appears on areas of lighter pigmentation that are not exposed to the sun; and typically, the tumors present as dark, rapidly spreading patches, according to Gloster and Neal. “In 25 to 50 percent of cases, these tumors arise within prior pigmented lesions,” they write.

“People don’t realize that they need to look at these areas,” says Dr. Taylor. “If there’s a dark mark or discoloration, then you have to bring it to the attention of your physician. If the physician discounts it, you should request a biopsy.” To health-care providers, she advises, “At the very least, you must ask your skin of color patients to take off their shoes and socks and inspect the feet, between the toes and the soles. That’s easy to do. We have to train the podiatrists. Also, internists will often look at their patients’ feet for signs of diabetes. We need to heighten their awareness of melanoma.”

Meanwhile, areas of chronic inflammation also bear watching for signs of skin cancer, says Jenna Lester, MD, an assistant professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. “I do a lot of education around that with my patients with discoid lupus or hidradenitis suppurativa,” she says. Gloster and Neal write that the most important risk factors for cSCC in Black people are sites of chronic inflammation and chronic scarring processes. The latter are noted in 20 to 40 percent of cases of cSCC in Blacks, and trouble spots include burn scars, areas of past physical or thermal trauma, ulcers and prior sites of radiation therapy. With regard to inflammation, Dr. Lester says, “Controlling it and the downstream effects of inflammation is important in preventing cancers in those particular situations.”

Spotting both cSCC and BCC in darker skin involves knowing they can be pigmented, or brown, says Dr. Taylor, “whereas in white skin, BCCs are commonly described as pink and pearly in color. So if you have a brown bump, as opposed to a pink, pearly bump, you might not think of BCC.”

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma also can present differently in skin of color, says Dr. Adamson. “It’s not as red.” Instead, what stands out is hypopigmentation, Dr. Lester elaborates. If not recognized, “It can lead to misdiagnosis of post-inflammatory hypopigmentation or eczema. It’s important to have that in your differential diagnosis when you’re considering hypopigmented patches in patients with dark skin.”

Pigmented BCC

BCC on the nose of an Asian man

It’s one thing to describe what to look for, and another to see it in photos. Dr. Taylor worked hard to address the need for more images in textbooks of skin cancer in skin of color. As artificial intelligence applications to diagnose these diseases are being developed, the urgency to address the image deficit grows, says Dr. Adamson, who is on the American Academy of Dermatology’s Task Force on Augmented Intelligence.

“Recently, a number of groups have come up with artificial intelligence-driven algorithms that can detect melanomas as well as, if not better than, dermatologists can. This means that it’s theoretically possible to have some type of app or technology where we could detect skin cancers early and intervene to save lives. That is the promise,” explains Dr. Adamson.

While stressing that these are his own opinions, and not representative of the task force’s positions, he continues, “The downside is that these algorithms have been trained on data [image] sources that have almost zero skin cancers in darker skin. Therefore, if this technology were to be broadly available, it could either underdiagnose, or misdiagnose and potentially delay detection of cancers in darker skin types. If you’re not training the algorithm with a diverse sample, you can’t then expect it to perform at that same level in a diverse group of patients.” Therefore, databases such as the International Skin Imaging Collaboration must add more images of skin of color.

Melanoma on the lip of a Black man. Photo credit: Carl V. Washington, MD

Melanoma on the eyebrow of a Hispanic man. Photo credit: R. Steven Padilla, MD

Dr. Lester adds that more such images in the media will benefit patients, too. She is a coauthor of a cross-sectional study of skin cancer prevention social media campaigns during May 2020 that is in-press in JAMA Dermatology. Nearly 73 percent of the at-risk individuals depicted in the campaigns they studied had Fitzpatrick I/II skin types, 18 percent had Fitzpatrick III/IV and fewer than 10 percent were Fitzpatrick V/VI. Further, only 1.7 percent of the social media posts had captions specifically mentioning skin cancer in skin of color.

“The point of that analysis was just to show that there is an under-representation of patients of color in skin cancer advertisements and messaging, and that’s something that we should pay attention to,” says Dr. Lester. “If you are an Indian person who looks at an article or advertisement and only sees white people, you may not feel like that article or that advertisement is speaking to you. You may skip over it. And if that advertisement is about skin cancer, or about mitigating your risk, or what signs and symptoms to look out for, you may miss that information.”

Bowen’s disease of the finger

Subungual melanoma

Perhaps the popularity of the Instagram account Brown Skin Matters, a crowd-sourced feed of images of disease in darker skin, is evidence of a desire by the general public to know more. Curated by a non-medical professional, it has more than 70,000 followers.

We should not assume we know enough yet about the risk factors for skin cancer in people of color, as well as the best protection measures, says Dr. Adamson. For instance, while it is gospel that people should protect themselves from ultraviolet (UV) light exposure to reduce their risk of developing melanoma, Dr. Adamson says there isn’t strong enough evidence that is true for people of color. He points to a newly published review of studies in JAMA Dermatology, of which he was a coauthor. The studies collectively included more than 7,700 cases of melanoma in skin of color, defined as having Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, non-white race or skin that rarely or never burns due to sun exposure. “Of the 13 studies that met inclusion criteria, 11 found no association between UV exposure and melanoma in skin of color. One study showed a small positive relationship in Black males, and one showed a weak association in Hispanic males. All studies were of moderate to low quality (Oxford Centre ratings 2b to 4),” wrote the authors. More research is needed to determine the risk factors for melanoma in skin of color, they concluded.

Dr. Adamson stresses that this doesn’t mean physicians should stop recommending sun protection measures for patients of color. As his study states, “Photoprotection may be associated with benefits in other UV-associated disorders, such as photoaging, melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.” He still recommends sun protection for his own patients of color. The physician also notes that patients of color may prefer chemical sunscreens — particularly tinted ones — to physical sunscreens such as titanium dioxide and zinc oxide, which can leave a pale and cosmetically undesirable cast on darker skin.

[Editor’s note: The R&D chemists in the sunscreen industry are working on innovations in mineral and tinted formulations that are cosmetically pleasing on many skin tones. More Black-owned businesses are marketing such products, too.]

It’s also important to listen to the concerns of patients of color, says Dr. Lester. “A common theme I hear is feeling misunderstood, disregarded or that their concerns weren’t taken seriously by physicians.” Because she is a person of color, she says some of her patients of color feel her exam office is “a space where they feel comfortable and can express their thoughts freely and feel like they will be addressed.”

Organizations such as the SOCS are working to bring more dermatologists and dermatology researchers into the field. As a result of heightened interest in addressing racial disparities, “Now we have a $100,000 grant for a young investigator,” Dr. Taylor says, “in addition to $15,000 grants for research within the area of skin of color.”

That’s not to say physicians who are white or don’t share a patient’s background can’t deliver the best care to that patient. Dr. Lester says there is a lot of information out there for dermatologists to educate themselves.

Bridging that divide and establishing trust is also important and can affect patients’ engagement beyond their skin health. Dermatology can be a gateway to the patient’s health care, she says. “If they have a good experience, they may say, ‘Well, hey, I’m going to listen to you. I have this other health issue, too,’ or, ‘I’ve been told my blood pressure is a problem. I’m ready to deal with that now.’

“I think it’s incredibly important that dermatologists see their role as not just taking care of the skin but perhaps a first instance in which the patient either turns toward or away from more medical care.”

Sheryl Huggins Salomon is a New York-based contributor to Everyday Health and Livestrong.com and has held editorial leadership positions at The Root, AOL Black Voices and NewsOne.com.

Note: The Skin Cancer Foundation is partnering with the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) to encourage physicians and institutions to donate photos of skin cancer in skin of color to this international public research database. ISIC was founded in 2015 by New York City dermatologist Allan C. Halpern, MD, a vice president of The Skin Cancer Foundation and co-editor of The Melanoma Letter.

Désirée Ratner, MD

Désirée Ratner, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Carcinomas & Keratoses

My Skin of Color Education Started with My Mohs Practice

Until I started practicing Mohs surgery at Columbia University Medical Center in upper Manhattan in the late 1990s, I never realized how little I knew about skin of color. Most of the Black and Asian patients I had operated on as a fellow in Boston had had small biopsy-proven pigmented basal cell carcinomas that looked a bit like seborrheic keratoses and were straightforward to treat. I had encountered multiple cSCCs in pigmented skin during my residency in Ann Arbor, in patients with discoid lupus erythematosus, lichen planus or a history of arsenic exposure. After all of those years of training, I thought I was prepared to handle anything.

Morpheaform BCC on a Black woman’s face

However, when a Black woman came to see me with an ulcerated morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on her scalp, treated for years with topical steroids and clindamycin, and soon thereafter, a Hispanic woman came in wondering why the pigmented BCC on her forehead had grown so large before it was biopsied, I was shocked — not because their tumors had gone undiagnosed for so long, as I had already treated my fair share of large tumors. What disturbed me was that the health-care providers who had monitored and treated them for years hadn’t recognized what they were looking at. More disturbing was the possibility that, without having printed biopsy results in front of me, maybe I wouldn’t have known what I was looking at, either.

Fortunately, I was able to clear both patients’ tumors with Mohs surgery and repair their defects on the same day. Unfortunately, both required skin grafts, which might not have been the case had their tumors been diagnosed earlier. My experiences in Washington Heights provided me with an invaluable education in recognizing and treating skin cancers in patients of color, which I hadn’t known I’d needed.

Nearly 10 years later, a CME article was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology entitled “Skin Cancer in Skin of Color,” detailing the incidence, risk factors and increased risks of morbidity and mortality in dark-skinned ethnic groups. By then, I had seen a multitude of patients with tumors not unlike those depicted in the manuscript, so the information presented was not surprising. Even so, the manuscript’s message hit home, bolstered by the reference predicting that by the year 2050, Hispanics, Asians and Blacks would represent 50 percent of the U.S. population. The numbers told the story: not only was skin cancer in people of color under-recognized and underreported, but unless people of all skin types were educated and properly evaluated by physicians who knew what they were looking for, the skin cancer epidemic would be impossible to fight. The authors of the paper had exposed not only a physician practice gap but also a patient education gap, and both needed to be addressed.

The dermatologists whose work is featured in this issue of Carcinomas & Keratoses are working to close these gaps. Drs. Taylor, Lester, Adamson and others have focused their efforts on educating health-care providers and the public about skin cancer detection and prevention in people of color. Their work highlights the importance of including more skin of color images in textbooks and databases for artificial intelligence applications, and in the media, and has shown that we need to refine our knowledge of skin cancer risk factors in pigmented skin to address the aforementioned gaps effectively.

There is still much work to do to decrease racial disparities and improve the outcomes of our patients with skin cancer. Given the extraordinary drive and abilities of the individuals working to solve these problems, I have no doubt that things will get better. For our patients’ sake, I’m hoping that success arrives sooner rather than later.

Review JDD’s 2020 special issue on skin of color: https://jddonline.com/issue?issue_id=271

Hear more from Dr. Lester on treating skin of color in this Science Friday podcast: https://www.sciencefriday.com/person/jenna-lester/

Learn more about skin color in dermatology textbooks: https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(20)30700-3/fulltext

Explore racial differences in time to treatment for melanoma: https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(20)30517-X/fulltext

Read about ethnicity impact on skin cancer knowledge and quality of life in patients with skin cancer: https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(20)30149-3/fulltext